ANIMAL NAVIGATION AND MIGRATION

ANIMAL NAVIGATION & MIGRATION

Introduction

Early research

Mechanisms

Remembered landmarks

Orientation by the Sun

Orientation by the night sky

Orientation by polarised light

Magnetoreception

Olfaction

Gravity receptors

Other senses

Way-marking

Path integration

Effects of human activity

MIGRATION

Animal navigation is the ability of many animals to find their way accurately without maps or instruments. Birds such as the Arctic tern, insects such as the monarch butterfly and fish such as the salmon regularly migrate thousands of miles to and from their breeding grounds, and many other species navigate effectively over shorter distances.

Dead reckoning, navigating from a known position using only information about one's own speed and direction, was suggested by Charles Darwin in 1873 as a possible mechanism. In the 20th century, Karl von Frisch showed that honey bees can navigate by the Sun, by the polarization pattern of the blue sky, and by the Earth's magnetic field; of these, they rely on the Sun when possible. William Tinsley Keeton showed that homing pigeons could similarly make use of a range of navigational cues, including the Sun, Earth's magnetic field, olfaction and vision. Ronald Lockley demonstrated that a small seabird, the Manx shearwater, could orient itself and fly home at full speed, when released far from home, provided either the Sun or the stars were visible.

Several species of animal can integrate cues of different types to orient themselves and navigate effectively. Insects and birds are able to combine learned landmarks with sensed direction (from the Earth's magnetic field or from the sky) to identify where they are and so to navigate. Internal 'maps' are often formed using vision, but other senses including olfaction and echolocation may also be used.

The ability of wild animals to navigate may be adversely affected by products of human activity. For example, there is evidence that pesticides may interfere with bee navigation, and that lights may harm turtle navigation.

Early research

In 1873, Charles Darwin wrote a letter to Nature magazine, arguing that animals including man have the ability to navigate by dead reckoning, even if a magnetic 'compass' sense and the ability to navigate by the stars is present:[2]

Later in 1873, Joseph John Murphy[b] replied to Darwin, writing back to Nature with a description of how he, Murphy, believed animals carried out dead reckoning, by what is now called inertial navigation:[3]

Karl von Frisch (1886–1982) studied the European honey bee, demonstrating that bees can recognize a desired compass direction in three different ways: by the Sun, by the polarization pattern of the blue sky, and by the Earth's magnetic field. He showed that the Sun is the preferred or main compass; the other mechanisms are used under cloudy skies or inside a dark beehive.[4]

William Tinsley Keeton (1933–1980) studied homing pigeons, showing that they were able to navigate using the Earth's magnetic field, the Sun, as well as both olfactory and visual cues.[5]

Donald Griffin (1915–2003) studied echolocation in bats, demonstrating that it was possible and that bats used this mechanism to detect and track prey, and to "see" and thus navigate through the world around them.[6]

Ronald Lockley (1903–2000), among many studies of birds in over fifty books, pioneered the science of bird migration. He made a twelve-year study of shearwaters such as the Manx shearwater, living on the remote island of Skokholm.[7] These small seabirds make one of the longest migrations of any bird—10,000 kilometres—but return to the exact nesting burrow on Skokholm year after year. This behaviour led to the question of how they navigated.[8]

Mechanisms

Lockley began his book Animal Navigation with the words:[9]

Many mechanisms of spatial cognition have been proposed for animal navigation: there is evidence for a number of them.[10][11] Investigators have often been forced to discard the simplest hypotheses - for example, some animals can navigate on a dark and cloudy night, when neither landmarks nor celestial cues like Sun, Moon, or stars are visible. The major mechanisms known or hypothesized are described in turn below.

Remembered landmarks

Animals including mammals, birds and insects such as bees and wasps (Ammophila and Sphex),[12] are capable of learning landmarks in their environment, and of using these in navigation.[13]

Orientation by the Sun

Some animals can navigate using celestial cues such as the position of the Sun. Since the Sun moves in the sky, navigation by this means also requires an internal clock. Many animals depend on such a clock to maintain their circadian rhythm.[14] Animals that use sun compass orientation are fish, birds, sea-turtles, butterflies, bees, sandhoppers, reptiles, and ants.[15]

When sandhoppers (such as Talitrus saltator) are taken up a beach, they easily find their way back down to the sea. It has been shown that this is not simply by moving downhill or towards the sight or sound of the sea. A group of sandhoppers were acclimatised to a day/night cycle under artificial lighting, whose timing was gradually changed until it was 12 hours out of phase with the natural cycle. Then, the sandhoppers were placed on the beach in natural sunlight. They moved away from the sea, up the beach. The experiment implied that the sandhoppers use the sun and their internal clock to determine their heading, and that they had learnt the actual direction down to the sea on their particular beach.[16]

Experiments with Manx shearwaters showed that when released "under a clear sky" far from their nests, the seabirds first oriented themselves and then flew off in the correct direction. But if the sky was overcast at the time of release, the shearwaters flew around in circles.[8]

Monarch butterflies use the Sun as a compass to guide their southwesterly autumn migration from Canada to Mexico.[15]

Orientation by the night sky

In a pioneering experiment, Lockley showed that warblers placed in a planetarium showing the night sky oriented themselves towards the south; when the planetarium sky was then very slowly rotated, the birds maintained their orientation with respect to the displayed stars. Lockley observes that to navigate by the stars, birds would need both a "sextant and chronometer": a built-in ability to read patterns of stars and to navigate by them, which also requires an accurate time-of-day clock.[17]

In 2003, the African dung beetle Scarabaeus zambesianus was shown to navigate using polarization patterns in moonlight, making it the first animal known to use polarized moonlight for orientation.[18][19][20][c] In 2013, it was shown that dung beetles can navigate when only the Milky Way or clusters of bright stars are visible,[22] making dung beetles the only insects known to orient themselves by the galaxy.[23]

Orientation by polarised light

Some animals, notably insects such as the honey bee, are sensitive to the polarisation of light. Honey bees can use polarized light on overcast days to estimate the position of the Sun in the sky, relative to the compass direction they intend to travel. Karl von Frisch's work established that bees can accurately identify the direction and range from the hive to a food source (typically a patch of nectar-bearing flowers). A worker bee returns to the hive and signals to other workers the range and direction relative to the Sun of the food source by means of a waggle dance. The observing bees are then able to locate the food by flying the implied distance in the given direction,[4] though other biologists have questioned whether they necessarily do so, or are simply stimulated to go and search for food.[24] However, bees are certainly able to remember the location of food, and to navigate back to it accurately, whether the weather is sunny (in which case navigation may be by the Sun or remembered visual landmarks) or largely overcast (when polarised light may be used).[4]

Magnetoreception

Some animals, including mammals such as blind mole rats (Spalax)[25] and birds such as pigeons, are sensitive to the Earth's magnetic field.[26]

Homing pigeons use magnetic field information with other navigational cues.[27] Pioneering researcher William Keeton showed that time-shifted homing pigeons could not orient themselves correctly on a clear sunny day, but could do so on an overcast day, suggesting that the birds prefer to rely on the direction of the Sun, but switch to using a magnetic field cue when the Sun is not visible. This was confirmed by experiments with magnets: the pigeons could not orient correctly on an overcast day when the magnetic field was disrupted.[28]

Olfaction

Olfactory navigation has been suggested as a possible mechanism in pigeons. Papi's 'mosaic' model argues that pigeons build and remember a mental map of the odours in their area, recognizing where they are by the local odour.[29] Wallraff's 'gradient' model argues that there is a steady, large-scale gradient of odour which remains stable for long periods. If there were two or more such gradients in different directions, pigeons could locate themselves in two dimensions by the intensities of the odours. However it is not clear that such stable gradients exist.[30] Papi did find evidence that anosmic pigeons (unable to detect odours) were much less able to orient and navigate than normal pigeons, so olfaction does seem to be important in pigeon navigation. However, it is not clear how olfactory cues are used.[31]

Olfactory cues may be important in salmon, which are known to return to the exact river where they hatched. Lockley reports experimental evidence that fish such as minnows can accurately tell the difference between the waters of different rivers.[32] Salmon may use their magnetic sense to navigate to within reach of their river, and then use olfaction to identify the river at close range.[33]

Gravity receptors

GPS tracing studies indicate that gravity anomalies could play a role in homing pigeon navigation.

Other senses

Biologists have considered other senses that may contribute to animal navigation. Many marine animals such as seals are capable of hydrodynamic reception, enabling them to track and catch prey such as fish by sensing the disturbances their passage leaves behind in the water.[36] Marine mammals such as dolphins,[37] and many species of bat,[6] are capable of echolocation, which they use both for detecting prey and for orientation by sensing their environment.

Way-marking

The wood mouse is the first non-human animal to be observed, both in the wild and under laboratory conditions, using movable landmarks to navigate. While foraging, they pick up and distribute visually conspicuous objects, such as leaves and twigs, which they then use as landmarks during exploration, moving the markers when the area has been explored.[38]

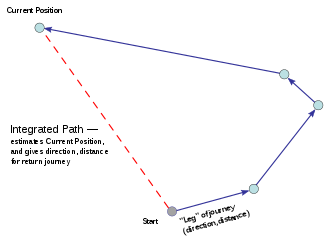

Path integration

Dead reckoning, in animals usually known as path integration, means the putting together of cues from different sensory sources within the body, without reference to visual or other external landmarks, to estimate position relative to a known starting point continuously while travelling on a path that is not necessarily straight. Seen as a problem in geometry, the task is to compute the vector to a starting point by adding the vectors for each leg of the journey from that point.[39]

Since Darwin's On the Origins of Certain Instincts[2] (quoted above) in 1873, path integration has been shown to be important to navigation in animals including ants, rodents and birds.[40][41] When vision (and hence the use of remembered landmarks) is not available, such as when animals are navigating on a cloudy night, in the open ocean, or in relatively featureless areas such as sandy deserts, path integration must rely on idiothetic cues from within the body.[42][43]

Studies by Wehner in the Sahara desert ant (Cataglyphis bicolor) demonstrate effective path integration to determine directional heading (by polarized light or sun position) and to compute distance (by monitoring leg movement or optical flow).[44]

Path integration in mammals makes use of the vestibular organs, which detect accelerations in the three dimensions, together with motor efference, where the motor system tells the rest of the brain which movements were commanded,[25] and optic flow, where the visual system signals how fast the visual world moves past the eyes.[45] Information from other senses such as echolocation and magnetoreception may also be integrated in certain animals. The hippocampus is the part of the brain that integrates linear and angular motion to encode a mammal's relative position in space.[46]

David Redish states that "The carefully controlled experiments of Mittelstaedt and Mittelstaedt (1980) and Etienne (1987) have demonstrated conclusively that [path integration in mammals] is a consequence of integrating internal cues from vestibular signals and motor efferent copy".[47]

Effects of human activity

Neonicotinoid pesticides may impair the ability of bees to navigate. Bees exposed to low levels of thiamethoxam were less likely to return to their colony, to an extent sufficient to compromise a colony's survival.[48]

Light pollution attracts and disorients photophilic animals, those that follow light. For example, hatchling sea turtles follow bright light, particularly bluish light, altering their navigation. Disrupted navigation in moths can easily be observed around bright lamps on summer nights. Insects gather around these lamps at high densities instead of navigating naturally

MIGRATION

Animal migration is the relatively long-distance movement of individual animals, usually on a seasonal basis. It is the most common form of migration in ecology. It is found in all major animal groups, including birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians, insects, and crustaceans. The cause of migration may be local climate, local availability of food, the season of the year or for mating.

To be counted as a true migration, and not just a local dispersal or irruption, the movement of the animals should be an annual or seasonal occurrence, or a major habitat change as part of their life. An annual event could include Northern Hemisphere birds migrating south for the winter, or wildebeest migrating annually for seasonal grazing. A major habitat change could include young Atlantic salmon or sea lamprey leaving the river of their birth when they have reached a few inches in size. Some traditional forms of human migration fit this pattern.

Migrations can be studied using traditional identification tags such as bird rings, or tracked directly with electronic tracking devices. Before animal migration was understood, folklore explanations were formulated for the appearance and disappearance of some species, such as that barnacle geese grew from goose barnacles.

Overview

Concepts

Migration can take very different forms in different species, and has a variety of causes.[2][3][4] As such, there is no simple accepted definition of migration.[5] One of the most commonly used definitions, proposed by the zoologist J. S. Kennedy[6] is

Migration encompasses four related concepts: persistent straight movement; relocation of an individual on a greater scale (in both space and time) than its normal daily activities; seasonal to-and-fro movement of a population between two areas; and movement leading to the redistribution of individuals within a population.[5] Migration can be either obligate, meaning individuals must migrate, or facultative, meaning individuals can "choose" to migrate or not. Within a migratory species or even within a single population, often not all individuals migrate. Complete migration is when all individuals migrate, partial migration is when some individuals migrate while others do not, and differential migration is when the difference between migratory and non-migratory individuals is based on discernible characteristics like age or sex.[5] Irregular (non-cyclical) migrations such as irruptions can occur under pressure of famine, overpopulation of a locality, or some more obscure influence.[7]

Seasonal

Seasonal migration is the movement of various species from one habitat to another during the year. Resource availability changes depending on seasonal fluctuations, which influence migration patterns. Some species such as Pacific salmon migrate to reproduce; every year, they swim upstream to mate and then return to the ocean.[8] Temperature is a driving factor of migration that is dependent on the time of year. Many species, especially birds, migrate to warmer locations during the winter to escape poor environmental conditions.[9]

Circadian

Circadian migration is where birds utilise circadian rhythm (CR) to regulate migration in both fall and spring. In circadian migration, clocks of both circadian (daily) and circannual (annual) patterns are used to determine the birds' orientation in both time and space as they migrate from one destination to the next. This type of migration is advantageous in birds that, during the winter, remain close to the equator, and also allows the monitoring of the auditory and spatial memory of the bird's brain to remember an optimal site of migration. These birds also have timing mechanisms that provide them with the distance to their destination.[10]

Tidal

Tidal migration is the use of tides by organisms to move periodically from one habitat to another. This type of migration is often used in order to find food or mates. Tides can carry organisms horizontally and vertically for as little as a few nanometres to even thousands of kilometres.[11] The most common form of tidal migration is to and from the intertidal zone during daily tidal cycles.[11] These zones are often populated by many different species and are rich in nutrients. Organisms like crabs, nematodes, and small fish move in and out of these areas as the tides rise and fall, typically about every twelve hours. The cycle movements are associated with foraging of marine and bird species. Typically, during low tide, smaller or younger species will emerge to forage because they can survive in the shallower water and have less chance of being preyed upon. During high tide, larger species can be found due to the deeper water and nutrient upwelling from the tidal movements. Tidal migration is often facilitated by ocean currents.[12][13][14]

Diel

While most migratory movements occur on an annual cycle, some daily movements are also described as migration. Many aquatic animals make a diel vertical migration, travelling a few hundred metres up and down the water column,[15] while some jellyfish make daily horizontal migrations of a few hundred metres.[16]

In specific groups

[edit]Different kinds of animals migrate in different ways.

In birds

[edit]

Approximately 1,800 of the world's 10,000 bird species migrate long distances each year in response to the seasons.[17] Many of these migrations are north-south, with species feeding and breeding in high northern latitudes in the summer and moving some hundreds of kilometres south for the winter.[18] Some species extend this strategy to migrate annually between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The Arctic tern has the longest migration journey of any bird: it flies from its Arctic breeding grounds to the Antarctic and back again each year, a distance of at least 19,000 km (12,000 mi), giving it two summers every year.[19]

Bird migration is controlled primarily by day length, signalled by hormonal changes in the bird's body.[20] On migration, birds navigate using multiple senses. Many birds use a sun compass, requiring them to compensate for the sun's changing position with time of day.[21] Navigation involves the ability to detect magnetic fields.[22]

In fish

[edit]

Most fish species are relatively limited in their movements, remaining in a single geographical area and making short migrations to overwinter, to spawn, or to feed. A few hundred species migrate long distances, in some cases of thousands of kilometres. About 120 species of fish, including several species of salmon, migrate between saltwater and freshwater (they are 'diadromous').[23][24]

Forage fish such as herring and capelin migrate around substantial parts of the North Atlantic ocean. The capelin, for example, spawn around the southern and western coasts of Iceland; their larvae drift clockwise around Iceland, while the fish swim northwards towards Jan Mayen island to feed and return to Iceland parallel with Greenland's east coast.[25]

In the 'sardine run', billions of Southern African pilchard Sardinops sagax spawn in the cold waters of the Agulhas Bank and move northward along the east coast of South Africa between May and July.[26]

In insects

[edit]

Some winged insects such as locusts and certain butterflies and dragonflies with strong flight migrate long distances. Among the dragonflies, species of Libellula and Sympetrum are known for mass migration, while Pantala flavescens, known as the globe skimmer or wandering glider dragonfly, makes the longest ocean crossing of any insect: between India and Africa.[27] Exceptionally, swarms of the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria, flew westwards across the Atlantic Ocean for 4,500 kilometres (2,800 mi) during October 1988, using air currents in the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone.[28]

In some migratory butterflies, such as the monarch butterfly and the painted lady, no individual completes the whole migration. Instead, the butterflies mate and reproduce on the journey, and successive generations continue the migration.[29]

In mammals

[edit]Some mammals undertake exceptional migrations; reindeer have one of the longest terrestrial migrations on the planet, reaching as much as 4,868 kilometres (3,025 mi) per year in North America. However, over the course of a year, grey wolves move the most. One grey wolf covered a total cumulative annual distance of 7,247 kilometres (4,503 mi).[30]

Mass migration occurs in mammals such as the Serengeti 'great migration',[31] an annual circular pattern of movement with some 1.7 million wildebeest and hundreds of thousands of other large game animals, including gazelles and zebra.[32][33] More than 20 such species engage, or used to engage, in mass migrations.[34] Of these migrations, those of the springbok, black wildebeest, blesbok, scimitar-horned oryx, and kulan have ceased.[35] Long-distance migrations occur in some bats – notably the mass migration of the Mexican free-tailed bat between Oregon and southern Mexico.[36] Migration is important in cetaceans, including whales, dolphins and porpoises; some species travel long distances between their feeding and their breeding areas.[37]

Humans are mammals, but human migration, as commonly defined, is when individuals often permanently change where they live, which does not fit the patterns described here. An exception is some traditional migratory patterns such as transhumance, in which herders and their animals move seasonally between mountains and valleys, and the seasonal movements of nomads.[38][39]

In other animals

Among the reptiles, adult sea turtles migrate long distances to breed, as do some amphibians. Hatchling sea turtles, too, emerge from underground nests, crawl down to the water, and swim offshore to reach the open sea.[40] Juvenile green sea turtles make use of Earth's magnetic field to navigate.[41]

Some crustaceans migrate, such as the largely-terrestrial Christmas Island red crab, which moves en masse each year by the millions. Like other crabs, they breathe using gills, which must remain wet, so they avoid direct sunlight, digging burrows to shelter from the sun. They mate on land near their burrows. The females incubate their eggs in their abdominal brood pouches for two weeks. Then they return to the sea to release their eggs at high tide in the moon's last quarter. The larvae spend a few weeks at sea and then return to land.[42][43]

Tracking Migration

Scientists gather observations of animal migration by tracking their movements. Animals were traditionally tracked with identification tags such as bird rings for later recovery. However, no information was obtained about the actual route followed between release and recovery, and only a fraction of tagged individuals were recovered. More convenient, therefore, are electronic devices such as radio-tracking collars that can be followed by radio, whether handheld, in a vehicle or aircraft, or by satellite.[44] GPS animal tracking enables accurate positions to be broadcast at regular intervals, but the devices are inevitably heavier and more expensive than those without GPS. An alternative is the Argos Doppler tag, also called a 'Platform Transmitter Terminal' (PTT), which sends regularly to the polar-orbiting Argos satellites; using Doppler shift, the animal's location can be estimated, relatively roughly compared to GPS, but at a lower cost and weight.[44] A technology suitable for small birds which cannot carry the heavier devices is the geolocator which logs the light level as the bird flies, for analysis on recapture.[45] There is scope for further development of systems able to track small animals globally.[46]

Radio-tracking tags can be fitted to insects, including dragonflies and bees.[47]

In culture

Before animal migration was understood, various folklore and erroneous explanations were formulated to account for the disappearance or sudden arrival of birds in an area. In Ancient Greece, Aristotle proposed that robins turned into redstarts when summer arrived.[48] The barnacle goose was explained in European Medieval bestiaries and manuscripts as either growing like fruit on trees, or developing from goose barnacles on pieces of driftwood.[49] Another example is the swallow, which was once thought, even by naturalists such as Gilbert White, to hibernate either underwater, buried in muddy riverbanks, or in hollow trees

"This Content Sponsored by Buymote Shopping app

BuyMote E-Shopping Application is One of the Online Shopping App

Now Available on Play Store & App Store (Buymote E-Shopping)

Click Below Link and Install Application: https://buymote.shop/links/0f5993744a9213079a6b53e8

Sponsor Content: #buymote #buymoteeshopping #buymoteonline #buymoteshopping #buymoteapplication"

Comments

Post a Comment